Dispersion (optics)

In optics, dispersion is the phenomenon in which the phase velocity of a wave depends on its frequency,[1] or alternatively when the group velocity depends on the frequency. Media having such a property are termed dispersive media. Dispersion is sometimes called chromatic dispersion to emphasize its wavelength-dependent nature, or group-velocity dispersion (GVD) to emphasize the role of the group velocity.

The most familiar example of dispersion is probably a rainbow, in which dispersion causes the spatial separation of a white light into components of different wavelengths (different colors). However, dispersion also has an effect in many other circumstances: for example, GVD causes pulses to spread in optical fibers, degrading signals over long distances; also, a cancellation between group-velocity dispersion and nonlinear effects leads to soliton waves. Dispersion is most often described for light waves, but it may occur for any kind of wave that interacts with a medium or passes through an inhomogeneous geometry (e.g., a waveguide), such as sound waves.

There are generally two sources of dispersion: material dispersion and waveguide dispersion. Material dispersion comes from a frequency-dependent response of a material to waves. For example, material dispersion leads to undesired chromatic aberration in a lens or the separation of colors in a prism. Waveguide dispersion occurs when the speed of a wave in a waveguide (such as an optical fiber) depends on its frequency for geometric reasons, independent of any frequency dependence of the materials from which it is constructed. More generally, "waveguide" dispersion can occur for waves propagating through any inhomogeneous structure (e.g., a photonic crystal), whether or not the waves are confined to some region. In general, both types of dispersion may be present, although they are not strictly additive. Their combination leads to signal degradation in optical fibers for telecommunications, because the varying delay in arrival time between different components of a signal "smears out" the signal in time.

Contents |

Material dispersion in optics

Material dispersion can be a desirable or undesirable effect in optical applications. The dispersion of light by glass prisms is used to construct spectrometers and spectroradiometers. Holographic gratings are also used, as they allow more accurate discrimination of wavelengths. However, in lenses, dispersion causes chromatic aberration, an undesired effect that may degrade images in microscopes, telescopes and photographic objectives.

The phase velocity, v, of a wave in a given uniform medium is given by

where c is the speed of light in a vacuum and n is the refractive index of the medium.

In general, the refractive index is some function of the frequency f of the light, thus n = n(f), or alternatively, with respect to the wave's wavelength n = n(λ). The wavelength dependence of a material's refractive index is usually quantified by its Abbe number or its coefficients in an empirical formula such as the Cauchy or Sellmeier equations.

Because of the Kramers–Kronig relations, the wavelength dependence of the real part of the refractive index is related to the material absorption, described by the imaginary part of the refractive index (also called the extinction coefficient). In particular, for non-magnetic materials (μ = μ0), the susceptibility  that appears in the Kramers–Kronig relations is the electric susceptibility

that appears in the Kramers–Kronig relations is the electric susceptibility  .

.

The most commonly seen consequence of dispersion in optics is the separation of white light into a color spectrum by a prism. From Snell's law it can be seen that the angle of refraction of light in a prism depends on the refractive index of the prism material. Since that refractive index varies with wavelength, it follows that the angle that the light is refracted by will also vary with wavelength, causing an angular separation of the colors known as angular dispersion.

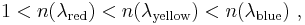

For visible light, refraction indices n of most transparent materials (e.g., air, glasses) decrease with increasing wavelength λ:

or alternatively:

In this case, the medium is said to have normal dispersion. Whereas, if the index increases with increasing wavelength (which is typically the case for X-rays), the medium is said to have anomalous dispersion.

At the interface of such a material with air or vacuum (index of ~1), Snell's law predicts that light incident at an angle θ to the normal will be refracted at an angle arcsin(sin(θ)/n). Thus, blue light, with a higher refractive index, will be bent more strongly than red light, resulting in the well-known rainbow pattern.

Group and phase velocity

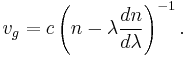

Another consequence of dispersion manifests itself as a temporal effect. The formula v = c / n calculates the phase velocity of a wave; this is the velocity at which the phase of any one frequency component of the wave will propagate. This is not the same as the group velocity of the wave, that is the rate at which changes in amplitude (known as the envelope of the wave) will propagate. For a homogeneous medium, the group velocity vg is related to the phase velocity by (here λ is the wavelength in vacuum, not in the medium):

The group velocity vg is often thought of as the velocity at which energy or information is conveyed along the wave. In most cases this is true, and the group velocity can be thought of as the signal velocity of the waveform. In some unusual circumstances, called cases of anomalous dispersion, the rate of change of the index of refraction with respect to the wavelength changes sign, in which case it is possible for the group velocity to exceed the speed of light (vg > c). Anomalous dispersion occurs, for instance, where the wavelength of the light is close to an absorption resonance of the medium. When the dispersion is anomalous, however, group velocity is no longer an indicator of signal velocity. Instead, a signal travels at the speed of the wavefront, which is c irrespective of the index of refraction.[3] Recently, it has become possible to create gases in which the group velocity is not only larger than the speed of light, but even negative. In these cases, a pulse can appear to exit a medium before it enters.[4] Even in these cases, however, a signal travels at, or less than, the speed of light, as demonstrated by Stenner, et al.[5]

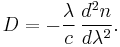

The group velocity itself is usually a function of the wave's frequency. This results in group velocity dispersion (GVD), which causes a short pulse of light to spread in time as a result of different frequency components of the pulse travelling at different velocities. GVD is often quantified as the group delay dispersion parameter (again, this formula is for a uniform medium only):

If D is less than zero, the medium is said to have positive dispersion. If D is greater than zero, the medium has negative dispersion. If a light pulse is propagated through a normally dispersive medium, the result is the higher frequency components travel slower than the lower frequency components. The pulse therefore becomes positively chirped, or up-chirped, increasing in frequency with time. Conversely, if a pulse travels through an anomalously dispersive medium, high frequency components travel faster than the lower ones, and the pulse becomes negatively chirped, or down-chirped, decreasing in frequency with time.

The result of GVD, whether negative or positive, is ultimately temporal spreading of the pulse. This makes dispersion management extremely important in optical communications systems based on optical fiber, since if dispersion is too high, a group of pulses representing a bit-stream will spread in time and merge together, rendering the bit-stream unintelligible. This limits the length of fiber that a signal can be sent down without regeneration. One possible answer to this problem is to send signals down the optical fibre at a wavelength where the GVD is zero (e.g., around 1.3–1.5 μm in silica fibres), so pulses at this wavelength suffer minimal spreading from dispersion—in practice, however, this approach causes more problems than it solves because zero GVD unacceptably amplifies other nonlinear effects (such as four wave mixing). Another possible option is to use soliton pulses in the regime of anomalous dispersion, a form of optical pulse which uses a nonlinear optical effect to self-maintain its shape—solitons have the practical problem, however, that they require a certain power level to be maintained in the pulse for the nonlinear effect to be of the correct strength. Instead, the solution that is currently used in practice is to perform dispersion compensation, typically by matching the fiber with another fiber of opposite-sign dispersion so that the dispersion effects cancel; such compensation is ultimately limited by nonlinear effects such as self-phase modulation, which interact with dispersion to make it very difficult to undo.

Dispersion control is also important in lasers that produce short pulses. The overall dispersion of the optical resonator is a major factor in determining the duration of the pulses emitted by the laser. A pair of prisms can be arranged to produce net negative dispersion, which can be used to balance the usually positive dispersion of the laser medium. Diffraction gratings can also be used to produce dispersive effects; these are often used in high-power laser amplifier systems. Recently, an alternative to prisms and gratings has been developed: chirped mirrors. These dielectric mirrors are coated so that different wavelengths have different penetration lengths, and therefore different group delays. The coating layers can be tailored to achieve a net negative dispersion.

Dispersion in waveguides

Optical fibers, which are used in telecommunications, are among the most abundant types of waveguides. Dispersion in these fibers is one of the limiting factors that determine how much data can be transported on a single fiber.

The transverse modes for waves confined laterally within a waveguide generally have different speeds (and field patterns) depending upon their frequency (that is, on the relative size of the wave, the wavelength) compared to the size of the waveguide.

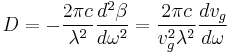

In general, for a waveguide mode with an angular frequency ω(β) at a propagation constant β (so that the electromagnetic fields in the propagation direction (z) oscillate proportional to  ), the group-velocity dispersion parameter D is defined as:[6]

), the group-velocity dispersion parameter D is defined as:[6]

where  is the vacuum wavelength and

is the vacuum wavelength and  is the group velocity. This formula generalizes the one in the previous section for homogeneous media, and includes both waveguide dispersion and material dispersion. The reason for defining the dispersion in this way is that |D| is the (asymptotic) temporal pulse spreading

is the group velocity. This formula generalizes the one in the previous section for homogeneous media, and includes both waveguide dispersion and material dispersion. The reason for defining the dispersion in this way is that |D| is the (asymptotic) temporal pulse spreading  per unit bandwidth

per unit bandwidth  per unit distance travelled, commonly reported in ps / nm km for optical fibers.

per unit distance travelled, commonly reported in ps / nm km for optical fibers.

A similar effect due to a somewhat different phenomenon is modal dispersion, caused by a waveguide having multiple modes at a given frequency, each with a different speed. A special case of this is polarization mode dispersion (PMD), which comes from a superposition of two modes that travel at different speeds due to random imperfections that break the symmetry of the waveguide.

Higher-order dispersion over broad bandwidths

When a broad range of frequencies (a broad bandwidth) is present in a single wavepacket, such as in an ultrashort pulse or a chirped pulse or other forms of spread spectrum transmission, it may not be accurate to approximate the dispersion by a constant over the entire bandwidth, and more complex calculations are required to compute effects such as pulse spreading.

In particular, the dispersion parameter D defined above is obtained from only one derivative of the group velocity. Higher derivatives are known as higher-order dispersion.[7] These terms are simply a Taylor series expansion of the dispersion relation  of the medium or waveguide around some particular frequency. Their effects can be computed via numerical evaluation of Fourier transforms of the waveform, via integration of higher-order slowly varying envelope approximations, by a split-step method (which can use the exact dispersion relation rather than a Taylor series), or by direct simulation of the full Maxwell's equations rather than an approximate envelope equation.

of the medium or waveguide around some particular frequency. Their effects can be computed via numerical evaluation of Fourier transforms of the waveform, via integration of higher-order slowly varying envelope approximations, by a split-step method (which can use the exact dispersion relation rather than a Taylor series), or by direct simulation of the full Maxwell's equations rather than an approximate envelope equation.

Dispersion in gemology

| Name | B–G | C–F |

|---|---|---|

| Cinnabar (HgS) | 0.40 | – |

| Synth. rutile | 0.330 | 0.190 |

| Rutile (TiO2) | 0.280 | 0.120–0.180 |

| Anatase (TiO2) | 0.213–0.259 | – |

| Wulfenite | 0.203 | 0.133 |

| Vanadinite | 0.202 | – |

| Fabulite | 0.190 | 0.109 |

| Sphalerite (ZnS) | 0.156 | 0.088 |

| Sulfur (S) | 0.155 | – |

| Stibiotantalite | 0.146 | – |

| Goethite (FeO(OH)) | 0.14 | – |

| Brookite (TiO2) | 0.131 | 0.12–1.80 |

| Zincite (ZnO) | 0.127 | – |

| Linobate | 0.13 | 0.075 |

| Synth. moissanite (SiC) | 0.104 | – |

| Cassiterite (SnO2) | 0.071 | 0.035 |

| Zirconia (ZrO2) | 0.060 | 0.035 |

| Powellite (CaMoO4) | 0.058 | – |

| Andradite | 0.057 | – |

| Demantoid | 0.057 | 0.034 |

| Cerussite | 0.055 | 0.033–0.050 |

| Titanite | 0.051 | 0.019–0.038 |

| Benitoite | 0.046 | 0.026 |

| Anglesite | 0.044 | 0.025 |

| Diamond (C) | 0.044 | 0.025 |

| Flint glass | 0.041 | – |

| Hyacinth | 0.039 | – |

| Jargoon | 0.039 | – |

| Starlite | 0.039 | – |

| Zircon (ZrSiO4) | 0.039 | 0.022 |

| GGG | 0.038 | 0.022 |

| Scheelite | 0.038 | 0.026 |

| Dioptase | 0.036 | 0.021 |

| Whewellite | 0.034 | – |

| Alabaster | 0.033 | – |

| Gypsum | 0.033 | 0.008 |

| Epidote | 0.03 | 0.012–0.027 |

| Achroite | 0.017 | – |

| Cordierite | 0.017 | 0.009 |

| Danburite | 0.017 | 0.009 |

| Dravite | 0.017 | – |

| Elbaite | 0.017 | – |

| Herderite | 0.017 | 0.008–0.009 |

| Hiddenite | 0.017 | 0.010 |

| Indicolite | 0.017 | – |

| liddicoatite | 0.017 | – |

| Kunzite | 0.017 | 0.010 |

| Rubellite | 0.017 | 0.008–0.009 |

| Schorl | 0.017 | – |

| Scapolite | 0.017 | – |

| Spodumene | 0.017 | 0.010 |

| Tourmaline | 0.017 | 0.009–0.011 |

| Verdelite | 0.017 | – |

| Andalusite | 0.016 | 0.009 |

| Baryte (BaSO4) | 0.016 | 0.009 |

| Euclase | 0.016 | 0.009 |

| Alexandrite | 0.015 | 0.011 |

| Chrysoberyl | 0.015 | 0.011 |

| Hambergite | 0.015 | 0.009–0.010 |

| Phenakite | 0.01 | 0.009 |

| Rhodochrosite | 0.015 | 0.010–0.020 |

| Sillimanite | 0.015 | 0.009–0.012 |

| Smithsonite | 0.014–0.031 | 0.008–0.017 |

| Amblygonite | 0.014–0.015 | 0.008 |

| Aquamarine | 0.014 | 0.009–0.013 |

| Beryl | 0.014 | 0.009–0.013 |

| Brazilianite | 0.014 | 0.008 |

| Celestine | 0.014 | 0.008 |

| Goshenite | 0.014 | – |

| Heliodor | 0.014 | 0.009–0.013 |

| Morganite | 0.014 | 0.009–0.013 |

| Pyroxmangite | 0.015 | – |

| Synth. scheelite | 0.015 | – |

| Dolomite | 0.013 | – |

| Magnesite (MgCO3) | 0.012 | – |

| Synth. emerald | 0.012 | – |

| Synth. alexandrite | 0.011 | – |

| Synth. sapphire (Al2O3) | 0.011 | – |

| Phosphophyllite | 0.010–0.011 | – |

| Enstatite | 0.010 | – |

| Anorthite | 0.009–0.010 | – |

| Actinolite | 0.009 | – |

| Jeremejevite | 0.009 | – |

| Nepheline | 0.008–0.009 | – |

| Apophyllite | 0.008 | – |

| Hauyne | 0.008 | – |

| Natrolite | 0.008 | – |

| Synth. quartz (SiO2) | 0.008 | – |

| Aragonite | 0.007–0.012 | – |

| Augelite | 0.007 | – |

| Tanzanite | 0.030 | 0.011 |

| Thulite | 0.03 | 0.011 |

| Zoisite | 0.03 | – |

| YAG | 0.028 | 0.015 |

| Almandine | 0.027 | 0.013–0.016 |

| Hessonite | 0.027 | 0.013–0.015 |

| Spessartine | 0.027 | 0.015 |

| Uvarovite | 0.027 | 0.014–0.021 |

| Willemite | 0.027 | – |

| Pleonaste | 0.026 | – |

| Rhodolite | 0.026 | – |

| Boracite | 0.024 | 0.012 |

| Cryolite | 0.024 | – |

| Staurolite | 0.023 | 0.012–0.013 |

| Pyrope | 0.022 | 0.013–0.016 |

| Diaspore | 0.02 | – |

| Grossular | 0.020 | 0.012 |

| Hemimorphite | 0.020 | 0.013 |

| Kyanite | 0.020 | 0.011 |

| Peridote | 0.020 | 0.012–0.013 |

| Spinel | 0.020 | 0.011 |

| Vesuvianite | 0.019–0.025 | 0.014 |

| Clinozoisite | 0.019 | 0.011–0.014 |

| Labradorite | 0.019 | 0.010 |

| Axinite | 0.018–0.020 | 0.011 |

| Ekanite | 0.018 | 0.012 |

| Kornerupine | 0.018 | 0.010 |

| Corundum (Al2O3) | 0.018 | 0.011 |

| Rhodizite | 0.018 | – |

| Ruby (Al2O3) | 0.018 | 0.011 |

| Sapphire (Al2O3) | 0.018 | 0.011 |

| Sinhalite | 0.018 | 0.010 |

| Sodalite | 0.018 | 0.009 |

| Synth. corundum | 0.018 | 0.011 |

| Diopside | 0.018–0.020 | 0.01 |

| Emerald | 0.014 | 0.009–0.013 |

| Topaz | 0.014 | 0.008 |

| Amethyst (SiO2) | 0.013 | 0.008 |

| Anhydrite | 0.013 | – |

| Apatite | 0.013 | 0.010 |

| Apatite | 0.013 | 0.008 |

| Aventurine | 0.013 | 0.008 |

| Citrine | 0.013 | 0.008 |

| Morion | 0.013 | – |

| Prasiolite | 0.013 | 0.008 |

| Quartz (SiO2) | 0.013 | 0.008 |

| Smoky quartz (SiO2) | 0.013 | 0.008 |

| Rose quartz (SiO2) | 0.013 | 0.008 |

| Albite | 0.012 | – |

| Bytownite | 0.012 | – |

| Feldspar | 0.012 | 0.008 |

| Moonstone | 0.012 | 0.008 |

| Orthoclase | 0.012 | 0.008 |

| Pollucite | 0.012 | 0.007 |

| Sanidine | 0.012 | – |

| Sunstone | 0.012 | – |

| Beryllonite | 0.010 | 0.007 |

| Cancrinite | 0.010 | 0.008–0.009 |

| Leucite | 0.010 | 0.008 |

| Obsidian | 0.010 | – |

| Strontianite | 0.008–0.028 | – |

| Calcite (CaCO3) | 0.008–0.017 | 0.013–0.014 |

| Fluorite (CaF2) | 0.007 | 0.004 |

| Hematite | 0.500 | – |

| Synth. cassiterite (SnO2) | 0.041 | – |

| Gahnite | 0.019–0.021 | – |

| Datolite | 0.016 | – |

| Tremolite | 0.006–0.007 | – |

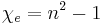

In the technical terminology of gemology, dispersion is the difference in the refractive index of a material at the B and G (686.7 nm and 430.8 nm) or C and F (653.3 nm and 486.1) Fraunhofer wavelengths, and is meant to express the degree to which a prism cut from the gemstone shows "fire", or color. Dispersion is a material property. Fire depends on the dispersion, the cut angles, the lighting environment, the refractive index, and the viewer.[8]

Dispersion in imaging

In photographic and microscopic lenses, dispersion causes chromatic aberration, which causes the different colors in the image not to overlap properly. Various techniques have been developed to counteract this, such as the use of achromats, multielement lenses with glasses of different dispersion. They are constructed in such a way that the chromatic aberrations of the different parts cancel out.

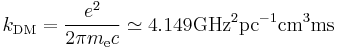

Dispersion in pulsar timing

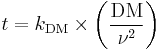

Pulsars are spinning neutron stars that emit pulses at very regular intervals ranging from milliseconds to seconds. Astronomers believe that the pulses are emitted simultaneously over a wide range of frequencies. However, as observed on Earth, the components of each pulse emitted at higher radio frequencies arrive before those emitted at lower frequencies. This dispersion occurs because of the ionised component of the interstellar medium, which makes the group velocity frequency dependent. The extra delay added at a frequency  is

is

where the dispersion constant  is given by

is given by

,

,

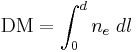

and the dispersion measure DM is the free electron column density (total electron content)  integrated along the path traveled by the photon from the pulsar to the Earth, and is given by

integrated along the path traveled by the photon from the pulsar to the Earth, and is given by

with units of parsecs per cubic centimetre (1pc/cm3 = 30.857×1021 m−2).[9]

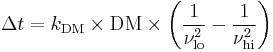

Typically for astronometric observations, this delay cannot be measured directly, since the emission time is unknown. What can be measured is the difference in arrival times at two different frequencies. The delay  between a high frequency

between a high frequency  and a low frequency

and a low frequency  component of a pulse will be

component of a pulse will be

Re-writing the above equation in terms of DM allows one to determine the DM by measuring pulse arrival times at multiple frequencies. This in turn can be used to study the interstellar medium, as well as allow for observations of pulsars at different frequencies to be combined.

See also

References

- ^ Born, Max; Wolf, Emil (October 1999). Principles of Optics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 14–24. ISBN 0521642221.

- ^ Calculation of the Mean Dispersion of Glasses

- ^ Brillouin, Léon. Wave Propagation and Group Velocity. (Academic Press: San Diego, 1960). See esp. Ch. 2 by A. Sommerfeld.

- ^ Wang, L.J., Kuzmich, A., and Dogariu, A. (2000). "Gain-assisted superluminal light propagation". Nature 406 (6793): 277. Bibcode 2000Natur.406..277W. doi:10.1038/35018520.

- ^ Stenner, M. D., Gauthier, D. J., and Neifeld, M. A. (2003). "The speed of information in a 'fast-light' optical medium". Nature 425 (6959): 695–8. Bibcode 2003Natur.425..695S. doi:10.1038/nature02016. PMID 14562097.

- ^ Rajiv Ramaswami and Kumar N. Sivarajan, Optical Networks: A Practical Perspective (Academic Press: London 1998).

- ^ Chromatic Dispersion, Encyclopedia of Laser Physics and Technology (Wiley, 2008).

- ^ a b Walter Schumann (2009). Gemstones of the World: Newly Revised & Expanded Fourth Edition. Sterling Publishing Company, Inc.. pp. 41–2. ISBN 978-1-4027-6829-3. http://books.google.com/books?id=V9PqVxpxeiEC&pg=PA42. Retrieved 31 December 2011.

- ^ Lorimer, D.R., and Kramer, M., Handbook of Pulsar Astronomy, vol. 4 of Cambridge Observing Handbooks for Research Astronomers, (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, U.K.; New York, U.S.A, 2005), 1st edition.

External links

- Optical Characteristics of the SF10 Crystal Prism

- Deviation Angle for a Prism

- Dispersive Wiki – discussing the mathematical aspects of dispersion.

- Dispersion – Encyclopedia of Laser Physics and Technology

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||